New computer...back online

Are you mad, blud?

333 on Friday was good despite what

prancehall and his shower click are saying. I went to the one late last year and this was a big improvement on that.

Ok so it didn’t do what it said on the tin (or flier) and there were some choking wastemen on the stage who cut some of the limelight from some of the real stars, but there were plenty of hype moments and I thought the crowd was pretty good. That said I left before three so things might’ve deteriorated thereafter. Highlights: the crowd filling in Skepta’s bars, Tempa T’s winding body and ‘swing’ bars, Fuda Guy bringing MCs onto the audience’s side of the barrier (when I though we might some grime-styled stage-diving), seeing All in One back in the scene again & Maximum’s set.

Big up Chantelle for putting the whole thing on. It may be a while before grime hones its live ‘product’ but that will come with time (and once mcs put themselves in the shoes of the audience and think about what they might want), but the priority for now is getting these nights ON.

Grime: locked out

Fuller version of my article appearing in Socialist Worker magazine:

Fuller version of my article appearing in Socialist Worker magazine:"I am a problem for Anthony Blair" (Dizzee Rascal, 2004)

Every generation has its youth movement, whether it's the psychedelic 60s, punk in the 70s, new wave in the 80s and dance music in the 90s. Grime is a current social phenomenon in London and predominantly elsewhere in the UK. A whole generation of young people from a part of society normally invisible to the mainstream unless labelled as "hoodies" or "gangs", have aspirations to be MCs, producers and DJs.

First to clarify, grime isn't a British version of US rap - a small UK hip hop scene has been running since the early 1990s but has failed to ignite because essentially it is a poor copy. Grime on the other hand comes from somewhere different because it has evolved from the rave, jungle and garage scenes, utilising the same infrastructure, personnel and context. Like it's wrong to describe Jamaican dancehall as a version of US hip hop (it emanated reggae), it is also wrong to view Grime as the same. Also, like jungle and garage before it, grime is essentially a London thing, though its influence is now spreading throughout the UK.

Despite all this, you won't see many 'grime' labelled nights if you scan the Time Out listings, because there aren't many nights running. The scene's live circuit is suppressed by Police and local authorities and has been since the early 00s.

While still known as ‘garage’, its main proponents - So Solid Crew - were targeted as principal enemies to the state by Ministers, tabloids and so on. A crew of 20 or so predominantly black males from a Battersea estate, rapping over harshly minimal beats reaching the upper echelons of the charts were not seen as wholesome entertainment by the powers that be, and certain misdemeanours involving their members, such as the carrying of firearms, supported their case. "Idiots like the So Solid Crew are glorifying gun culture and violence," said minister Kim Howells following the deaths of two Birmingham teenagers from gunfire in 2003.

This state-sponsored anti-garage lobby had enough clout to effectively shut down the live scene, ward off major label interest and dampen interest from the music media. Radio 1 lost interest, HMV stopped stocking the records, and music critics, fine with tales of gangster lives in US rap, were seemingly less keen to hear about the same issues played out on their doorstep.

’Grime’ was borne out of the suppression of the garage scene (though a strictly non-MC version of garage continues to prosper in clubs). Pirate radio, which was always a important conduit for jungle and garage, became even more important for grime when the other outlets closed. With the pressure to succeed being less about populating the dancefloor, the sounds became more experimental and MC lyrics became more serious, occasionally nihilistic and combined street slang with patois and cockney. Pay As You Go Kartel signified the mood with their underground hit "Terrible" – “now we're going on terrible, I've had enough that's it, now we're going on terrible”.

With less reliance on nightclubs, the scene also attracted a younger audience many of whom were brought up on a staple of US rap, Jamaican dancehall and UK garage. Self-made DVDs became an important currency in the scene - rappers, producers and DJs, deprived on a place on music television were given a platform to provide a visual accompaniment to their narratives. New underground stars have emerged in the last 3 to 4 years, Dizzee Rascal, Wiley, Kano and D Double. Some parts of the media have started taken an interest again in their perennial search for the next big thing. But the glass ceiling is still in place, in particular there is still very little evidence of a re-emerging live circuit. Eskimo Dance organised by central-figure Wiley was an extremely popular grime night, but after only a short run it has been pushed outside of London's M25 orbital to towns like Watford, Hemel and Chelmsford because of difficulties in securing permissions and licensees from authorities in London. In October 2005, Kano, a new major label signing from the grime scene, had his gig at the Scala in King's Cross cancelled following safety risk concerns from Camden Council and the Met Police. Similarly, MoBo award-winner, Sway was banned from the Jazz Cafe, in north London, after a fight which didn't involve the artist.

Indeed to an outsider, the live grime night would appear to have a certain level of rowdiness, but in this sense it is not too dissimilar to punk. Crews of young black and white teenagers leap around with their hoods up calling for the DJ to rewind a tune. Like punk though at its heartbeat is a positive instrument of disaffected youngsters organising themselves to question the way things are.

Perhaps it is this bit which is unpalatable in need of what could only be described as censorship? Police are openly advising promoters to remove "dangerous" acts from their line-ups. My own attempt to organise a mild community street festival in Hackney last August resulted in a police warning me it would be permitted so long as there would be "no garage, no rap, no reggae, no r'n'b" - not even an obscured subtext about who they didn't want to see there (presumably healthy music staples like death metal were deemed fine). Another example of grime's prohibition was the nightclub ban of the 'grime' anthem “pow” by Lethal Bizzle (a top ten chart hit) by police in Essex in 2004 because of the energetic reaction it caused on the dancefloor. Even pirate radio, grime's trusted media has received a clampdown by authorities, with over 40 transmitters confiscated near the end of 2005 on the very dubious basis that they interfere with emergency vehicle radio signals.

Major labels have cherry-picked talent (such as Dizzee Rascal) and in doing so have attempted through their marketing to de-contextualise and 'clean-up' their 'product' for mass consumption. This is to be expected I guess (de-rigueur for the ‘mainstream’), but it has further alienated grime's core audience.

Meanwhile mainstream music in the UK is become wilfully dominated by middle and upper class offspring in retro tribute bands - where the bad boy antics of the likes of Pete Doherty are hardly feared or suppressed, rather celebrated in the great tradition of rock and roll. Then there’s the tedious minstrels like James Blunt (staunch Thatcherite, ex-squaddie) or Katie Melua for example - showing how the music industry has become gentrified into bland theraputic soundtracks.

Music providing a voice for the disaffected, alienated and angry is not being tolerated at the moment, possibly because that anger, alienation and disaffection is a little too real. Without doubt, grime lyrics can be unpleasant, homophobic, misogynist and celebratory of gun culture, but it's so easy for the authorities/media to blame the plight and alienation of urban communities on means of expression and reflection (music) rather than examining what their own role might be in this. Tony Blair wants a little respect with his latest policy agenda, while Dizzee tells us 'you people are going to respect me if it kills you'.

Canvassing punters

Myspace is the place

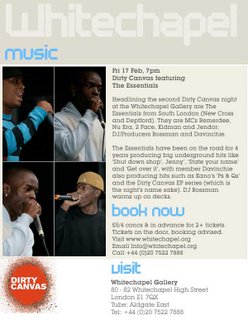

The Dirty Canvas night is just a few weeks away (17th Feb with the Essentials - for details scroll down) and has its very own myspace site

here, already with some very influential 'friends' .

Nik Cohn's 'The Trickster'

I read this over the Christmas holiday and really liked it (big up Tony Collins for passing it to me). It’s the story of Cohn, a middle-aged Ulsterman with a background in (mainly sixties) rock journalism, taking up residence in New Orleans’ projects in the late 90s and slowly immersing himself in the local bounce/rap scene…this culminates in him playing an executive producer role for some recordings and playing middleman between local rap acts (Choppa, Che Muse, Junie Bezel, Jahbo) and the mainstream music industry (this all taking place shortly before the hurricane and flooding last summer).It’s engagingly written though his hang-ups sometimes become tiresome. The book written to celebrate life in the downtown “ward” communities, and about the local “bounce” rap scene, but it often seemed to be about Cohn’s own acceptance into those communities and the ‘rap game’ than anything else. But that said, he did brilliantly illuminate life (and death) there, and how boundless aspirations (usually) morphed into desperate despair.

Regeneration Breakdown

This from a piece I wrote for The Eel fanzine

“There are areas and sections of the community that experience significant disadvantages typically in terms of high unemployment, low incomes, high benefit dependency, high crime and low educational attainment. If these areas are to continue to prosper the Council needs to remove barriers to business growth, enable disadvantaged communities to share the benefits of sustainable economic growth and offer a pleasant and safe place to live and work. These are the Council's regeneration challenges.” London Borough of Hackney 2005

Ask someone at the Council about the goings on at Tony’s café and the whys and wherefores of the Wratton deal and at some point they’ll mention the word ‘regeneration’.

Regeneration has become one of those catch-all phrases that was rarely used in the past, now it crops up everywhere from stem cell research to Dr Who. Perhaps it’s most common use has been on all those utopian-pictured and corporately-badged billboards hiding new brownfield development sites and on their accompanying pamphlets stuffed through our letterboxes. The intended message goes something like “things here are changing for the better – we represent progress!”. The difficulty when reading these things is getting a handle on what is being planned, why is it happening and perhaps more importantly who are the “we”?

Unfortunately the digger you deep the more complex ‘regeneration’ becomes. London is a quagmire of regeneration partnerships, Government quango agencies, strategic bodies and alliances, housing associations and that’s even before you get a-looking at the 33 London Borough and their typically idiosyncratic (re)structures. Each has their own mission statement and targets, each claim to be working with each other and each claim to represent the interests of people.

This latter point is important because it raises an interesting question about 'accountability' and the erosion of local democracy. All of these bodies, partnerships and strategic alliances are desperate to involve

‘the people’, you ‘

the residents’, because it helps to legitimise their work, telling their funders and partners that you, the masses, are on their side and so long may they continue. In return you get to make some ‘choices’ – choices because we are in so much love with shopping and consumerism, we are desperate for decisions about public services to be made in the same way. The trouble is that for regeneration the important choices tend to be made elsewhere and the

presented choices are highly doctored and simplified, amounting to no more than a colour preference. Increasingly these optional consumer choices are replacing the impact that people can make at the ballot box.

Back to the ‘regeneration’ which as I said earlier is a catch-all term. Defined simply in this context, ‘

regeneration’ is the response to something which is in a process of decline. This can be an area which is physically in a poor state of repair, and/or has a poor state of economy, and/or has a poor state of social well-being. Regeneration programmes aren’t necessarily about property schemes, they can also be as much about health projects, community safety initiatives, employment schemes and community development work. In fact there are some Government-sponsored schemes that are working reasonably well, but, rather than singing from the rafters about them, the Government keep quiet about them for fear of looking a bit, y’know, ‘leftie’.

But there’s also plenty of dross…. many schemes are promoted as

last chance saloon opportunities for the poor but are really concerned with easing the conscience of the wider population.

‘We’re doing something for them’ makes some voters believe we have a compassionate re-working of capitalism in this country. For others, the belief that poor people have been given every opportunity to climb out of their situation and yet have failed to do so has led to this now ritualistic castigation of them as sub-human (see the media-propelled “chav” label).

Then there is commercially-motivated regeneration – or

'economic development', still following the Thatcherite ethos that if you bring money into an area, it will somehow trickle down to the people who really need it. But a short stroll through the Poplar community overshadowed by the adjacent Canary Wharf will show this not to be true. Capital, rather than flowing or even tricking, has a tendency to stay (and grow) in the hands of the people who already have it.

For the major regeneration schemes though, the thing that has always kind of saved London in recent decades has been the difficulty for planners, developers and regenerators act on a more strategic scale – thereby limiting approaches to composite schemes within each of the 33 boroughs. This has helped London escape those strategically master-planned schemes that have helped blight so many provincial cities and sometimes turned them into identikit towns. Compared to this, London has progressed with in a slightly more distinct and organic piecemeal style. This though is changing and two major schemes will have a significant affect on East London in coming years. The first is the 2012 Olympics project, the second is the Thames Gateway scheme.

The Olympics project I won’t dwell on, but the computer aided designs show a huge ripple sculpting a huge part of East London into what looks like a huge monolithic golf course….let’s see, maybe more on that another time. The Thames Gateway is both more interesting and altogether much more significant, as it threatens to change the composition and distribution of communities in the city. The project – which is already underway – is seeking to build houses for up to a million people adjacent to the Thames between Newham in inner London stretching out to Thurrock in Essex. Several ‘

new towns’, ‘

urban villages’ and ‘

sustainable communities’ will be created in the process – for example Barking Reach will be a new 200,000 population town built on the river between Barking and Dagenham. Most of the housing is intended to be “affordable”, which means it will be targeted at those people currently renting from the Council or housing association, key workers (like teacher and nurses) or first time buyers. The process is being led by the London Development Agency (the economic development arm of the Greater London Authority) together with a number of specially set-up Urban Development Corporations (arms-length management companies in a similar vein to the London Dockland Development Corporation set up to develop Canary Wharf). The barely concealed agenda is to free up inner London’s land from social housing, and inject further pace into the gentrification process, bringing in more economic activity and creative buzz into London so that it can’t continue to compete as a “world class city”.

Council’s are already playing their part in the deal by helping to break up their social housing stock and selling it off to housing associations and anyone else who might be interested.. Then when the packaged homes promotions come, the flight will begin and inner London (like inner Paris) will be the preserve of the middle classes, with social problems out of sight, the sirens out of earshot.

So what can we do to stop Broadway Market and the rest of Hackney and the East End becoming this homogenised Theme Park for the professional classes? I would point to three areas to support:

1. Developing a voice for the area with strong local support. As we have seen countless times through London and elsewhere, where there’s a vacuum in support for local interests, politicians, regeneration strategists and developers will have it all their own way. Critically, this ‘voice’ must be able to articulate its own vision for the area even if this involves

‘leaving things as they are’.

2. Use the Council’s own institutional powers - A nagging concern I have regarding laying the boot into local Councils is that it is dangerously swimming with the tide. The Government is keen to do away with local government and is doing all it can to set government-authored bodies to take its place. Big business is no fan either. The danger in highlighting the corruption in one inner London borough might just help bring its longer-term extinction (to be replaced by more of the quango bodies). Therefore working to make the Council more accountable and less corruptible should be a goal itself.

3. Raise awareness of local economic patterns to show which patterns of spend are having a positive and detrimental impact on residents’ preferred vision for the area. Note: lining the pockets of the niche-trade organic lifestyle framer driving down in their SUV from Oxfordshire may not always represent the most ethical consumer decision.

While still known as ‘garage’, its main proponents - So Solid Crew - were targeted as principal enemies to the state by Ministers, tabloids and so on. A crew of 20 or so predominantly black males from a Battersea estate, rapping over harshly minimal beats reaching the upper echelons of the charts were not seen as wholesome entertainment by the powers that be, and certain misdemeanours involving their members, such as the carrying of firearms, supported their case. "Idiots like the So Solid Crew are glorifying gun culture and violence," said minister Kim Howells following the deaths of two Birmingham teenagers from gunfire in 2003.

While still known as ‘garage’, its main proponents - So Solid Crew - were targeted as principal enemies to the state by Ministers, tabloids and so on. A crew of 20 or so predominantly black males from a Battersea estate, rapping over harshly minimal beats reaching the upper echelons of the charts were not seen as wholesome entertainment by the powers that be, and certain misdemeanours involving their members, such as the carrying of firearms, supported their case. "Idiots like the So Solid Crew are glorifying gun culture and violence," said minister Kim Howells following the deaths of two Birmingham teenagers from gunfire in 2003. Meanwhile mainstream music in the UK is become wilfully dominated by middle and upper class offspring in retro tribute bands - where the bad boy antics of the likes of Pete Doherty are hardly feared or suppressed, rather celebrated in the great tradition of rock and roll. Then there’s the tedious minstrels like James Blunt (staunch Thatcherite, ex-squaddie) or Katie Melua for example - showing how the music industry has become gentrified into bland theraputic soundtracks.

Meanwhile mainstream music in the UK is become wilfully dominated by middle and upper class offspring in retro tribute bands - where the bad boy antics of the likes of Pete Doherty are hardly feared or suppressed, rather celebrated in the great tradition of rock and roll. Then there’s the tedious minstrels like James Blunt (staunch Thatcherite, ex-squaddie) or Katie Melua for example - showing how the music industry has become gentrified into bland theraputic soundtracks.

I read this over the Christmas holiday and really liked it (big up Tony Collins for passing it to me). It’s the story of Cohn, a middle-aged Ulsterman with a background in (mainly sixties) rock journalism, taking up residence in New Orleans’ projects in the late 90s and slowly immersing himself in the local bounce/rap scene…this culminates in him playing an executive producer role for some recordings and playing middleman between local rap acts (Choppa, Che Muse, Junie Bezel, Jahbo) and the mainstream music industry (this all taking place shortly before the hurricane and flooding last summer).It’s engagingly written though his hang-ups sometimes become tiresome. The book written to celebrate life in the downtown “ward” communities, and about the local “bounce” rap scene, but it often seemed to be about Cohn’s own acceptance into those communities and the ‘rap game’ than anything else. But that said, he did brilliantly illuminate life (and death) there, and how boundless aspirations (usually) morphed into desperate despair.

I read this over the Christmas holiday and really liked it (big up Tony Collins for passing it to me). It’s the story of Cohn, a middle-aged Ulsterman with a background in (mainly sixties) rock journalism, taking up residence in New Orleans’ projects in the late 90s and slowly immersing himself in the local bounce/rap scene…this culminates in him playing an executive producer role for some recordings and playing middleman between local rap acts (Choppa, Che Muse, Junie Bezel, Jahbo) and the mainstream music industry (this all taking place shortly before the hurricane and flooding last summer).It’s engagingly written though his hang-ups sometimes become tiresome. The book written to celebrate life in the downtown “ward” communities, and about the local “bounce” rap scene, but it often seemed to be about Cohn’s own acceptance into those communities and the ‘rap game’ than anything else. But that said, he did brilliantly illuminate life (and death) there, and how boundless aspirations (usually) morphed into desperate despair.